Pericardiocentesis is the aspiration of fluid from the pericardial space that surrounds the heart. This procedure can be life saving in patients with cardiac tamponade, even when it complicates acute type A aortic dissection and when cardiothoracic surgery is not available.

Cardiac tamponade is a time sensitive, life-threatening condition that requires prompt diagnosis and management. Historically, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade has been based on clinical findings. Claude Beck, a cardiovascular surgeon, described two triads of clinical findings that he found associated with acute and chronic cardiac tamponade. The first of these triads consisted of hypotension, an increased venous pressure, and a quiet heart. It has come to be recognized as Beck's triad, a collection of findings most commonly produced by acute intrapericardial hemorrhage. Subsequent studies have shown that these classic findings are observed in only a minority of patients with cardiac tamponade.

The detection of pericardial fluid has been facilitated by the development and continued improvement of echocardiography. Cardiac ultrasonography is now accepted as the criterion standard imaging modality for the assessment of pericardial effusions and the dynamic findings consistent with cardiac tamponade. With echocardiography, the location of the effusion can be identified, the size can be estimated (small, medium, or large), and the hemodynamic effects can be examined by assessing for abnormal septal motion, right atrial or right ventricular inversion, and decreased respiratory variation of the diameter of the inferior vena cava.

Moreover, a 2017 retrospective study (2007-2012) of 18 nontrauma patients diagnosed with large pericardial effusions or tamponade in an emergency department suggests that point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) may be effective in identifying pericardial effusions and guiding appropriate treatment, with a resultant decreased time to pericardiocentesis and decreased length of hospital stay.

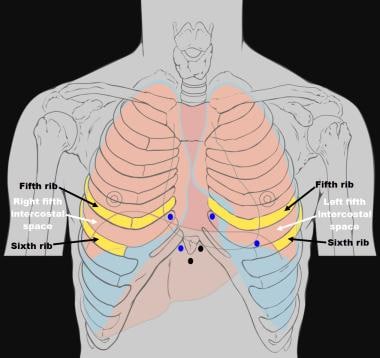

Subxiphoid views of pericardial effusion are shown below.

|

| Pericardiocentesis. Subxiphoid view of the heart demonstrating a moderate sized pericardial effusion. |

This article describes the landmark or “blind” syringe and needle technique used as a lifesaving measure for the prompt management of cardiac tamponade. Although a retrospective study has reported success and no complications with a novel pericardiocentesis technique that uses an in-plane parasternal medial-to-lateral approach with the use of a high-frequency probe in 11 patients with cardiac tamponade, larger studies and further investigation are needed.

Historical background

Percutaneous pericardiocentesis was introduced during the 19th century. Frank Schuh first described this procedure in 1840. By the 20th century, percutaneous pericardiocentesis became a preferred technique for the treatment of patients with pericardial effusion or for diagnostic purposes.

Before the advent of 2-dimensional echocardiography, the procedure used a blind-subxiphoid approach. Serious complications were not uncommon (eg, injury to liver, myocardium, coronary arteries, lungs). Because 2-dimensional echocardiography permits direct visualization of cardiac structures and adjacent vital organs, the procedure now is performed with minimal risk. Since 1979, echo-guided pericardiocentesis has been the preferred initial procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of most pericardial effusions. The technique has been modified and refined in the past 22 years. Percutaneous pericardiocentesis now is the procedure of choice for the safe removal of pericardial fluid. Whenever possible, this procedure should be performed by a surgeon, an interventional cardiologist or a cardiologist trained in invasive techniques.

There is no significant difference in overall mortality between open surgical drainage and percutaneous pericardiocentesis for symptomatic pericardial effusions. There may be more procedural complications following surgical drainage of a pericardial effusion, and the need for repeat procedures may be greater if the effusion is drained using pericardiocentesis.

Indications

Emergent pericardiocentesis

The indication for emergent pericardiocentesis is the presence of life-threatening hemodynamic changes in a patient with suspected cardiac tamponade.

Nonemergent pericardiocentesis

The aspiration of pericardial fluid in hemodynamically stable patients for diagnostic, palliative, or prophylactic reasons, performed under ultrasonography, computerized tomography, or fluoroscopic visualization.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications

In the hemodynamically unstable patient, no absolute contraindications exist to performing pericardiocentesis. The withdrawal of even a small amount of pericardial fluid may dramatically improve the patient’s hemodynamic status.

Relative contraindications

Relative contraindications include uncorrected bleeding disorders and traumatic cardiac tamponade. Some authors argue that traumatic cardiac tamponade should be treated by emergent thoracotomy.

Equipment

Essential equipment includes the following:

Antiseptic solutionSterile drapes, gown, and mask

Local anesthetic (eg, lidocaine 1%)

Syringes, 10 mL and 60 mL

Scalpel, No. 11

Needles, 18 ga, 1.5 in; 25 ga, 5/8 in

Spinal needle, 18 ga, 7.5-12 cm

Recommended equipment includes the following:

Commercially produced pericardiocentesis kitNasogastric tube

Ultrasound machine

Sterile ultrasound probe cover

Alligator clip connector for connection to V1 lead of ECG machine

Technique

Patient positioning

Position the patient in a semirecumbent position at a 30- to 45-degree angle. This position brings the heart closer to the anterior chest wall.

The supine position is an acceptable alternative.

Emergent needle pericardiocentesis

For patients too sick to be transferred to the catheterization laboratory, note the following:

Ensure that the patient has at least one established intravenous access line, is receiving supplemental oxygen, and is connected to a cardiac monitor and continuous pulse oximetry. If time permits, placement of a nasogastric tube to decompress the stomach and decrease the risk of gastric perforation is strongly recommended.Identify the anatomic landmarks (xiphoid process, 5th and 6th ribs, shown below) and select a site for needle insertion. The most commonly used sites are the left sternocostal margin or the subxiphoid approach.

|

| Pericardiocentesis. Pericardiocentesis needle insertion sites. The subxiphoid and the left sternocostal margin are the most commonly used sites (black dots). Adapted image from Wikimedia Commons/Patrick J Lynch, Medical Illustrator, and C Carl Jaffe, MD, Cardiologist. |

Use the antiseptic solution to clean and surgically prepare the subxiphoid area. If time allows, put on sterile gloves, gown, and mask, and then apply sterile drapes to delineate the surgical site.

Infiltrate local anesthetic solution at the chosen site by first creating a skin wheal and then infiltrating the subcutaneous and deeper tissues.

Puncture the skin using a No. 11 blade scalpel at the chosen site (between the xiphoid process and the left sternocostal margin).

Connect a 20-mL or 60-mL syringe to the spinal needle, and aspirate 5 mL of normal saline into the syringe. While advancing the needle, the occasional injection of up to 1 mL of normal saline may ensure that the needle lumen remains patent. If time permits, connect an alligator clip from the base of the spinal needle to the V1 lead of an ECG machine.

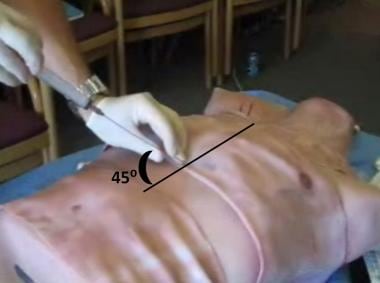

Insert the spinal needle through the skin incision and direct it toward the left shoulder. Maintain the needle at a 45-degree angle to the abdominal wall and 45 degrees off the midline sagittal plane as shown below. If time permits, needle insertion should be performed under direct ultrasonographic guidance.

|

| Pericardiocentesis. Needle insertion: Insert the spinal needle through the skin incision directed toward the left shoulder at a 45-degree angle to the abdominal wall and 45 degrees off the midline sagittal plane. |

Slowly advance the spinal needle up to a depth of 5 cm, as shown below, while applying negative pressure on the syringe until a return of fluid is visualized, cardiac pulsations are felt, or an abrupt change in the ECG waveform is noted. If the ECG waveform shows an injury pattern (ST segment elevation), then slowly withdraw the needle until the pattern returns to normal, as this change in waveform suggests that the spinal needle is in direct contact with the myocardium.

|

| Pericardiocentesis. Needle insertion: Slowly advance the spinal needle up to a depth of 5 cm while applying negative pressure on the syringe until a return of fluid is visualized. |

Withdraw as much fluid as possible; when the syringe is filled, stabilize the needle against the patient’s torso, remove the filled syringe, and replace it with another one. An alternative setup to replacing syringes is using a 3-way stopcock and intravenous tubing, which allows the physician to aspirate pericardial fluid into the syringe and, after turning the stopcock, eject the fluid into a basin or a collection bag. As pericardial fluid is aspirated, the needle may move closer to the heart, and if an injury pattern appears on the ECG waveform, then the needle should be slowly withdrawn.

Fluoroscopic- or ultrasonographic-guided pericardiocentesis with placement of a pericardial drain

Note the following:

Ensure that the patient is sitting at 30-45° head elevation, which increases pooling of fluid toward the inferior and anterior surface, thus maximizing fluid drainage.Select a site that is closest to the pericardial space, avoiding vital structures, such as the internal mammary artery, lungs, myocardium, liver, and vascular bundle at the inferior margin of each rib.

If hemorrhagic fluid is aspirated, a few milliliters of contrast medium are injected, which can be observed surrounding the cardiac silhouette, indicating that the needle tip is in the pericardial space. If the contrast material immediately disappears, then the needle is in one of the cardiac chambers.

Pericardiocentesis with fluoroscopy also appears to be an effective alternative method to treat postoperative pericardial effusion with accurate localization of the catheter in challenging situations, such as when contrast echocardiography may not be efficient due to surgical artefacts and pulmonary problems.

Pearls

Confirmation of pericardial versus intracardiac needle tip placement

Various techniques have been described, but none is more reliable than real-time, direct ultrasonographic guidance. Note the following:

Clotting: Intracardiac blood forms a clot, whereas pericardial aspirate should not form a clot.Hematocrit or hemoglobin measurement: The pericardial aspirate should have a lower hemoglobin concentration than the patient’s peripheral blood.

Fluorescein test: Intracardiac injection of fluorescein should cause a fluorescent flush on examination of the eyelid’s conjunctiva.

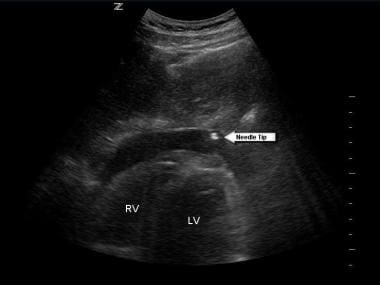

Seldinger technique

When patients with large pericardial effusions present in extremis due to the development of tamponade physiology, consider placing an indwelling pericardial catheter in order to allow further aspiration of fluid and to "buy time" if such patients cannot be taken to the operating room in a timely fashion.

Various commercial pericardiocentesis kits using the Seldinger technique exist. Review of the kit and its specific instructions is highly recommended prior to attempting placement.

The technique is similar to that of placing a central venous catheter. It is imperative to know that the needle tip is within the pericardial space and not within the heart before passing the guidewire and inserting the dilator. Ultrasonographic guidance, as shown below, is highly recommended.

|

| Pericardiocentesis. Subxiphoid view of the heart demonstrating the needle tip within the pericardial space. |

Complications

Coronary artery puncture or aneurysm

Left internal mammary artery puncture or aneurysm

Hemothorax

Pneumothorax

Pneumopericardium

Hepatic injury

False-negative aspiration – Clotted blood in the pericardium

False-positive aspiration – Intracardiac aspiration

Reaccumulation of pericardial fluid

0 Comments