Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a condition in which urine backwashes back up in the ureters/kidneys from the bladder. Urine will typically flow from the kidneys, drain down the ureters and then get stored in the bladder.

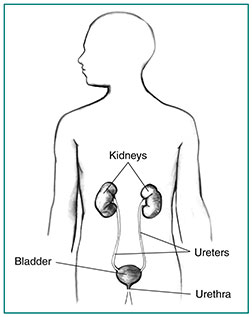

The urinary tract is your body’s drainage system for removing waste and extra water. Normally urine flows downward through the main structures of the urinary tract. These structures and what they do are:

- Kidneys: Two bean-shaped, fist-sized organs — one on each side of the spine below the rib cage — filter the body’s blood, producing urine.

- Ureters: Two thin, muscular tubes — one from each kidney — carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

- Bladder: The hollow, balloon-shaped organ located between the pelvic bones, which expands to store urine.

- Urethra: The thin tube at the bottom of the bladder through which urine exits the body. The male urethra is located in the penis and the female urethra ends in the vulvar area.

In VUR, urine flows back — refluxes — into one or both of your ureters and, in some cases, to one or both kidneys. VUR that affects only one ureter and kidney is called unilateral reflux. VUR that affects both ureters and kidneys is called a bilateral reflux. Looking at the medical words “vesicoureteral reflux,” “vescio” refers to the bladder while “ureteral” refers to the ureters. “Reflux,” means backup or back flow. Thus, vesicoureteral reflux is about back flow between the bladder and the ureters.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) mostly affects newborns, infants and young children ages two and under, but older children and (rarely) adults can also be affected. Children who have abnormal kidneys or urinary tracts are more likely to have VUR. The condition is more common in girls than in boys.

How common is vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

About 1% to 3% of children have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). There appears to be a hereditary link to the disorder. If one child in the family has VUR, there’s a little more than a one in four chance that a sibling will also have the condition. If a parent had VUR, there is a one in three chance that their child will have VUR.

Primary VUR due to a shortened ureter

What are the types of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

The two types of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) are “primary” and “secondary.” Most cases of VUR are primary and more commonly affects only one ureter and kidney. With primary VUR, a child is born with a ureter that did not implant into the bladder properly. The flap-valve formed between the ureter and the bladder wall does not close properly, so urine refluxes from the bladder to the ureter and, in some children, even backs up to the kidney. This type of VUR can get better as your child gets older. Fortunately, as your child grows, the intramuscular tunnel length gets longer, which can then improve the efficacy of the flap-valve.

Secondary VUR occurs when a blockage in the urinary tract causes an increase in pressure and pushes urine back up from the urethra into your child’s bladder, ureters and even kidneys. The blockage could result from an abnormal fold of tissue in the urethra that keeps urine from flowing freely out of your child’s bladder. Another cause of secondary VUR might be a problem with nerves that cannot stimulate the bladder to release urine. Children with secondary VUR often have bilateral reflux.

The Urinary Tract

How does the vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) grading system work?

The grades are one through five. Five is the most severe form of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). The grading system is based on how far the urine backs up into the urinary tract and on the width of the ureter(s).

- Grade One: The urine goes backwards up into a ureter that is normal in size.

- Grade Two: The urine backs up into the kidney’s pelvis area through a normal-sized ureter. Neither the kidney pelvis (the large, funnel-like end of the ureter through which the urine drains from the kidney into the ureter) nor the calyces (the kidney’s urine collection reservoir; directs the urine into the kidney pelvis) have gotten larger in size.

- Grade Three: The ureter(s), kidney pelvis and calyces are mild to moderately enlarged due to the backup of urine.

- Grade Four: The ureter(s) are curved and dilated, moderately, and the kidney pelvis and calyces are also moderately dilated because of too much urine.

- Grade Five: The ureter(s) are extremely distorted and enlarged. The kidney pelvis and calyces are very large from an extreme amount of urine retained in them.

SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES

What are the symptoms of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

In many cases, a child with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) has no symptoms. When symptoms are present, the most common is a urinary tract infection (UTI). UTIs are commonly caused by VUR. It is estimated that some 30% to 50% of children with UTI have VUR. VUR can lead to bladder and kidney infections because urine that remains in your child’s urinary tract provides a place for bacteria to grow.

What are the symptoms of a urinary tract infection?

Urinary tract infections (UTI) often result from VUR. If your child has symptoms of a UTI, they may also have VUR. Symptoms of a UTI include:

- Fever.

- Burning or pain when urinating.

- Pain in the lower abdomen.

- Pain in the lower or upper back.

- The need to urinate more often.

- Only a few drops come out when trying to urinate.

- Bladder leakage.

- Urine that is cloudy and smells badly.

Is vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) painful?

No, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is not painful. However, if there is a urinary tract infection, that can come with pain during urination and pain in the kidney/flank region.

What causes vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

The two types of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), primary and secondary, have different causes.

Primary VUR: The most common cause of primary VUR in children is an abnormal ureter. The flap-valve between your child’s ureter and bladder does not close efficiently, so urine backs up toward the kidney. As your child grows, the organs and structures mature and the valve may close correctly and primary VUR may improve.

Secondary VUR: The most common cause of secondary VUR is a blockage by a tissue or narrowing in the bladder neck or urethra. These problems cause urine to back up into the urinary tract instead of exiting through the urethra. A child may also have nerves to the bladder that don’t work as well as they should. That problem can keep the bladder from contracting and relaxing normally. Urine isn’t released in a coordinated way. Bilateral VUR — as opposed to unilateral — is more common with secondary VUR.

What causes vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in adults?

Adults with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) typically have had benign prostate hypertrophy, neurogenic bladder, or they have had surgery in the regions of the body near the ureters.

Can vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) cause kidney stones?

Yes. Urolithiasis is the formation of stony concretions in the bladder or urinary tract. Those concretions, or stones, are called different names based on the location. So, there can be kidney stones, ureteral stones, or bladder stones. Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) can cause those stones.

What are the complications of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

Complications of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in children include:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs), including bladder and kidney infections.

- Bladder problems including urinary incontinence, bedwetting and urinary retention.

- Constipation.

- High blood pressure.

- Kidney scarring, kidney damage (nephrotic syndrome) chronic kidney failure (rarely).

- Most children with VUR who get a UTI recover without long-term complications.

Is vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) life-threatening?

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) itself is not life-threatening. However, VUR can lead to recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), which can result in renal scarring (kidney scarring) and then worsen into renal hypertension (high blood pressure caused by kidney disease) and renal (kidney) disease. End-stage kidney disease requires dialysis and/or a transplant. Without those interventions, kidney disease is fatal.

How is vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) diagnosed?

The most common imaging tests used to diagnosed vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) include:

- Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG): VCUG is an x-ray image of the bladder and urethra taken before, during and after urination, which is also called voiding. A small catheter is placed into the urethra and is used to fill your child’s bladder with a special dye that can be seen by x-ray. The x-rays show if urine is flowing backward from the bladder into the ureters. The procedure is performed in a healthcare provider’s office, outpatient center, or hospital. Anesthesia is not needed, but sedation may be used for some children.

- Radionuclide cystogram (RNC): RNC is a type of nuclear scan that involves placing radioactive material into your child’s bladder. A scanner then detects the radioactive material as your child urinates or after the bladder is empty. The procedure is performed in a health care provider’s office, outpatient center, or hospital by a specially trained technician, and the images are interpreted by a radiologist. Anesthesia is not needed, but sedation may be used for some children. RNC is more sensitive than VCUG but does not provide as much detail of the bladder anatomy.

- Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan: This imaging test reveals if scars have developed in your child’s kidney as a result of a UTI in the kidney. This scan is usually recommended when a kidney ultrasound is abnormal.

- Ultrasound: This safe and painless imaging technique uses sound waves to create images of your child’s entire urinary tract, including the kidneys and bladder, however does not give detail about the grade of VUR. The study is performed in a health care provider’s office, outpatient center, or hospital. Anesthesia is not needed. Ultrasound may be used before a VCUG or RNC if you or your healthcare provider want to avoid exposure to x-ray radiation or radioactive material.

Ultrasound testing is usually done on:

- Infants diagnosed during pregnancy (while they’re in the womb) with urine blockage affecting the kidneys.

- Children younger than five years of age with a UTI.

- Children with a UTI and fever, called febrile UTI, regardless of age.

- Males with a UTI who are not sexually active, regardless of age or fever.

- Children with a family history of VUR, including an affected sibling.

- Children five years of age and older with a UTI.

What other tests do children with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) need?

If your child has been diagnosed with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), he or she should have the following tests:

- Blood pressure checks: Kidney problems puts a child at higher risk for high blood pressure.

- Blood tests: High levels of protein or creatinine (a normal waste product of muscle breakdown) are signs of kidney damage.

- Urine tests and culture: Protein in the urine is a sign of kidney damage; bacteria in the urine is a sign of infection.

Children with VUR should also be assessed for bladder/bowel dysfunction (BBD).

Symptoms of bowel and bladder problems include:

- Having to urinate often or suddenly.

- Long periods of time between bathroom visits.

- Daytime wetting.

- Pain in the penis or perineum (the area between the anus and genitals).

- Posturing to prevent wetting.

- Constipation (three or fewer bowel movements a week).

- Fecal incontinence (lack of control of bowel movements).

Children who have VUR along with any BBD symptoms are at greater risk of kidney damage due to infection.

How is vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) managed?

There are no home remedies or over-the-counter drugs that help manage vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Managing VUR requires the help of a healthcare provider. Treatment options depend on your child’s age, symptoms, type of VUR and its severity. Treatments include antibiotics and other medications, an injectable dissolvable bulking agent, short-term catheterization and surgery. You and your pediatrician and specialists will discuss these treatment options and make the best choice for your child’s VUR.

How is primary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) treated?

As your child gets older and their urinary tract anatomy grows and matures, primary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) will often improve on its own. Until then, your healthcare provider will prescribe an antibiotic to treat a urinary tract infection (UTI), if one is present. UTIs can lead to bladder and kidney infections.

Use of long-term antibiotics for the prevention of UTI, however, is somewhat controversial. Extended use of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance, meaning the medication will no longer work against the infection. This makes infections harder to fight and leads to the need to take different and potentially stronger drugs with more side effects.

Currently, the American Urological Association recommends antibiotic use under these specific conditions:

- Children younger than one year of age: Continuous antibiotics should be used if your child has a history of UTI and fever or if your child has a UTI without fever with VUR grade three through five identified through screening.

- Children older than one year of age with bladder/bowel dysfunction (BBD): Continuous antibiotics should be used while BBD is being treated.

- Children older than one year of age without BBD: Continuous antibiotics can be used at the discretion of the healthcare provider but is not automatically recommended; however, UTIs should be promptly treated.

Other medications

Two types of medications — angiotension converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers — are commonly used to treat high blood pressure. Controlling blood pressure slows kidney damage.

Surgery

Surgery is considered for children who have VUR with repeat UTIs, especially if there is kidney scarring and severe reflux. However, some healthcare providers recommend surgery when a scan of the kidneys shows evidence of scarring alone. The decision to correct VUR is not taken lightly and careful consideration and patient selection is necessary for the best outcome.

Several surgical approaches can be used to correct the connection between the ureters and bladder to prevent urine from refluxing.

The gold standard procedure for surgical correction of VUR is called a ureteral reimplant. The goal of the reimplant is to create a flap-valve mechanism, which means re-routing the ureter in the bladder wall with an appropriate length tunnel so that urine does not reflux back up into the ureter. This can be performed a number of different ways including an open approach (small abdominal incision) by either opening the bladder (intravesical) or performing it just outside the bladder (extravesical). Similarly, this same approach can be done robotic-assisted in a select subset of patients. Typically, these patients have an overnight stay and go home the next day.

Another type of procedure for primary VUR is the use of hyaluronic acid/dextranome (Deflux®), a gel-like liquid containing complex sugars, is an alternative to surgery for treatment of VUR. During this 30-minute procedure, a small amount of Deflux is injected into your child’s bladder wall near the opening of the ureter. This injection creates a bulge in the tissue and acts like a valve that makes it harder for urine to flow back up the ureter. However, urine can still flow forward into the urethra. Deflux is slowly broken down by your child’s body. It is replaced by your child’s own tissue as your child grows, keeping the tunnel length intact. Deflux injection is an outpatient procedure done under general anesthesia, so your child can go home the same day. Most of the risks are those related to using a cystoscope, a special camera used to see inside the bladder during the procedure.

Possible side effects/complications from the above procedures include:

- Swelling.

- Bruising

- Bladder irritation.

- Bleeding.

- Infection.

- Failure of the procedure.

Call your child’s healthcare provider after the procedure if your child:

- Hasn’t gone to the bathroom to urinate in eight to 10 hours.

- Has pain when urinating more than two days after the procedure.

- Refuses to go to the bathroom to urinate.

- Has severe pain in the belly/back/flank.

- Has a fever higher than 101.5 degrees F (38.6 degrees C).

- Has worsening bladder spasms that do not decrease within 24 hours.

- Vomits a lot.

- Has pain in the back and hips.

How is secondary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) treated?

Secondary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is treated by removing the blockage or improving how the bladder empties which is causing the reflux. Treatment may include:

- Surgery to remove a blockage or correct an abnormal bladder or ureter.

- Antibiotics to prevent or treat a UTI.

- Intermittent catheterization (draining the bladder of urine by inserting a thin tube, called a catheter, through the urethra to the bladder).

- Bladder muscle medication.

There is no known way to prevent vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) — not with food, lifestyle changes or drugs. However, there are steps you can take to improve your child’s overall urinary tract health. Make sure your child:

- Drinks enough water.

- Gets his/her diaper changed immediately when soiled.

- Urinates regularly.

- Gets treated for constipation and urinary or fecal incontinence as soon as possible.

Help your child to be healthy in every way. Encourage exercise and make sure meals are balanced and nutritious.

What can I expect if my child has vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

Expect your child to endure one or more urinary tract infections (UTIs) and/or BBD (bladder/bowel dysfunction). It is highly likely that your child will have UTIs first, and then later be diagnosed with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Most children outgrow the reflux completely, however some do not. These families work with their medical teams to come up with the best approach for their child.

How long will my child have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

Your child should have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) for less than a year. Your healthcare provider will likely insist on surgery if VUR isn’t resolved by the one year mark.

Can my child go to school with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

The answer to this question depends on the severity of the symptoms. Remember, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) itself isn’t disruptive to your child’s day to day living, but the urinary tract infections can be. Although not contagious, your child may be in pain or have problems with constipation or incontinence. Meet with your healthcare provider to discuss options for returning to school and participating in playdates.

What is it like living with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

The vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) will cause your child no pain or discomfort. You won’t even know your child has VUR until there’s a problem that has clear symptoms, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI).

When should I see my healthcare provider about vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)?

See your child’s pediatrician if you suspect a urinary tract infection. If the vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is discovered as the cause of the UTI/renal scarring, it will likely be treated and close monitoring and other treatments may need to be considered. Your pediatrician may send you to a specialist. A pediatric nephrologist is an expert who treats children with kidney issues and a pediatric urologist is an expert in surgery on the genital and urinary tracts.

How do I take care of my child?

Follow everything your healthcare provider recommends regarding vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Do everything you can to keep your child’s urinary tract healthy, including enough drinking water. Change your infant’s diaper right away when soiled and watch for infrequent urination. Remember, to protect your child’s kidneys you must do what you can to prevent urinary tract infections.

What questions should I ask my healthcare provider?

Have a conversation with your healthcare provider where you get answers to all of your questions about vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Recommended questions include:

- Is this a UTI or VUR?

- Is this BBD or VUR?

- Will my child’s primary VUR get better without treatment?

- Does my child also have kidney problems?

- Should I see a specialist?

- How will you treat my child’s VUR?

- What are the consequences of untreated VUR?

- What can I do at home to improve my child’s condition?

- Will this condition cause my child pain?

- How can I prevent a urinary tract infection?

- How can I prevent BBD?

- Should my other children be checked for VUR?

0Comments