Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder characterized by the restriction of energy intake which leads to significantly low body weight. Thought to have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric condition, the average age of onset is 15 years, with approximately 80-90% of those diagnosed being female. It is twice as common in teenage girls, and those with the disorder typically have an extreme fear of putting on weight coupled with a distorted body image, and an inability to understand the seriousness of their low body weight.

What Causes Anorexia?

Research has highlighted a range of environmental, psychological, intrapersonal and biological factors thought to influence the onset of AN.

Abnormalities in Reward Pathways

Research suggests that abnormalities in the food reward systems may be associated with AN. Functional brain imaging studies have found that recovered AN participants had an increased salience attribution to aversive and rewarding food stimuli compared to those without AN. Furthermore, structural brain imaging studies have shown alterations in the regions of the brain involved in reward pathways in those with AN.

Genetic Causes

Family and twin studies have indicated that genetics may play a role in the onset of AN. Gene analysis and imaging studies, in particular, have shown that anorexia is more likely to be developed in families with competitive, obsessive, and perfectionist personality traits.

Social Media and Societal Pressures

The use of social media platforms and exposure to television and fashion magazines is thought to be linked to the onset of AN due to the internalization of thin body types. Social media, in particular, combines traditional media with the potential for peer interaction. This propagation of stereotypes amongst peers may increase the risk of developing maladaptive eating behaviors. For example, research has found that a third of all anorexia-related video content could be viewed as “pro-anorexia”, and when compared to other videos discussing the consequences of AN, “pro-anorexia” videos had higher viewer ratings.

Further research has highlighted that maladaptive use of sites such as Facebook whereby individuals compare themselves to others is linked with an increase in body dissatisfaction and maladaptive eating behaviors.

Research has shown that anorexia can be developed as a coping mechanism in response to family conflicts, transitions, and academic pressures.

Signs and Symptoms of Anorexia

There is a range of signs and symptoms of anorexia; these include:

- Ritualistic behavior towards eating

- Skipping meals, avoiding foods considered fattening or eating very little

- Sleep disturbances

- Believing that losing a significant amount of weight is positive

- The development of lanugo (fine, downy hair)

- Dry skin and hair loss

- Lack of circulation in hands and feet

- Reduced libido

- Extreme fear of gaining weight

In addition to this, there is a range of signs that could indicate that a loved one has anorexia. These include:

- Trying to conceal their weight by wearing baggy or loose clothing

- Avoiding eating around others

- Lying about their weight, and when and how much they’ve eaten

- Significant weight loss

- Eating slowly or cutting their food into smaller pieces to try to hide how little they’re consuming.

One of the main psychological features of anorexia is the significant overvaluation of weight and shape. While individuals with anorexia tend to restrict their food intake, they may also partake in excessive exercise to burn a large number of calories. For example, they may prefer to stand rather than sit and take part in dance, athletics, and sports. Some may use diuretics and laxatives to reduce their weight even further. Typically, those diagnosed with anorexia may take part in “body checking” whereby they repeatedly measure, weigh, and view themselves in the mirror. These behaviors may allow them to be reassured that they are still thin.

Long-term Effects of Anorexia

AN is associated with a range of medical complications which can account for approximately more than half of all deaths of those with the disorder.

Immunological

The neuroendocrine system controls immune function. Those with AN have been found to have significant hormonal imbalances resulting in changes to their immune system. Most complications affect the major organ systems but can cause other issues such as hypothermia, hypotension, and bradycardia. Complications can occur due to malnutrition and weight loss. For example, starvation can result in fat and protein catabolism which causes the loss of cellular function and volume. This can effect and lead to atrophy of the muscles, liver, intestines, heart and kidneys.

Dermatological

As malnutrition continues, those with AN may develop dry skin which can bleed and fissure particularly around the toes and fingers. Furthermore, acrocyanosis can occur whereby the patient develops a cold intolerance resulting in a blueish discoloration of the ears, fingers and nose. This can occur due to the shunting of blood towards the central organs in response to hypothermia often seen in those with AN.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a health condition whereby the bones become less dense and more likely to fracture. Research has found that those with anorexia are more likely to develop the condition due to hormonal and nutritional deficits. In particular, women with anorexia may stop synthesizing estrogen, which can lead to an extreme loss in bone density. Furthermore, those with the disorder typically produce more of the stress hormone, cortisol, which has also been associated with bone loss.

In males, lack of testosterone, weight loss, and nutritional deficits are thought to explain the occurrence of osteoporosis.

Gastrointestinal

If body weight drops 15-20% below ideal body weight, then gastroparesis can occur whereby there is the delayed emptying of the stomach. This can manifest in symptoms of upper stomach pain, and bloating. If symptoms are not detected in a timely manner, then significant dilation of the stomach can lead to gastric necrosis, death, or perforation.

Anemia

One study examining the hematological complications of anorexia in females found that just under a fifth of them had anemia. Untreated anemia can cause issues with the immune system due to the lack of iron, which means that those with anorexia and anemia may be more at risk of developing infections and illnesses. Other risks include complications affecting the lungs or heart.

Diagnosing Anorexia

Clinicians will review the symptoms presented and refer to The fifth edition of The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) to make a diagnosis. The DSM-5 outlines the symptoms of AN, which are classified by severity, type, and status.

A) Restriction of energy intake which leads to significantly low body weight in relation to physical health, age, sex, and developmental trajectory.

B) The individual presents an intense fear of becoming fat or putting on weight. Persistent behaviors present that prevents weight gain despite being at an extreme low weight.

C) The individual has a distortion in the way they view their shape or body weight or a reduced ability to recognize the seriousness of their low body weight.

The DSM-5 defines a significantly low weight as one that is less than minimally normal for adults and minimally expected for adolescents and children.

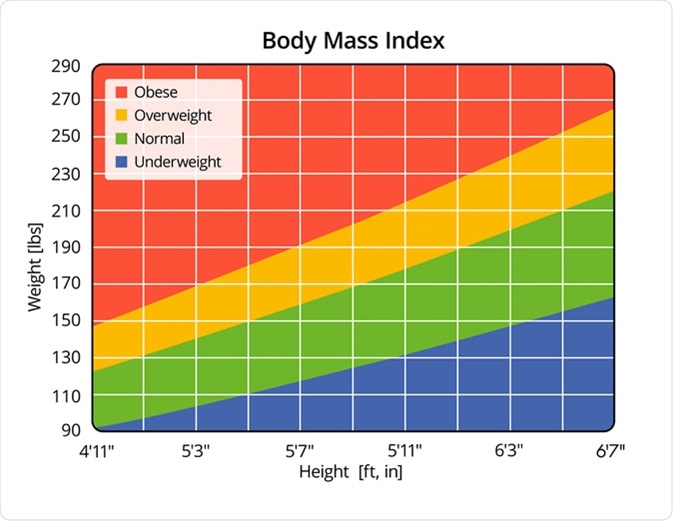

Once the review has been done, the severity of the symptoms will also be specified which for adolescents and children is based on body mass index (BMI) percentile, and for adults, on their current BMI. In addition to BMI, severity can be increased dependent on clinical symptoms, the need for supervision, and the level of functional disability.

Levels of Severity

- Mild: BMI>- 17 kg/m2

- Moderate: BMI 16-16.99 kg/m2

- Severe: BMI 15-15.99 kg/m2

- Extreme: BMI < 15 kg/m2

Treatment for Anorexia

It’s essential to begin treatment as soon as possible, to reduce the likelihood of developing serious health complications associated with starvation and the mental component of the disorder. A combination of supervised weight gain and therapy is often offered to address maladaptive thinking patterns. Treatments differ between young people and children, and those over 18.

Therapy for Children and Young People

Therapy for those under 18 includes family-centered therapy, adolescent-focused psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

- During family therapy, the patient and family members will discuss how anorexia affects them and explore ways in which the family can support and help prevent relapse.

- Through adolescent-focused psychotherapy, a therapist will assist the patient in exploring causes, strategies for prevention, and the implications of undereating.

- CBT helps patients to make better food choices, become more aware of the health consequences and risks of starvation, and ultimately help them cope with their feelings. The therapist may also support the patient in the creation of a personalized treatment plan.

Therapy for Adults

Therapy for adults with AN includes specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM), Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA), focal psychodynamic therapy, and CBT.

- Through SSCM, a therapist will assist the patient in understanding the causes of their AN, and provide nutritional advice in addition to helping the patient understand the link between their eating habits and AN.

- MANTRA involves exploring and better understanding the causes of the patient’s anorexia. It has a particular focus on what is important for each individual as well as assisting them in changing their behavior when they feel psychologically ready.

- Focal psychodynamic therapy is often offered if the patient doesn’t consider the other options right for them or if the alternatives have been unsuccessful. It aims to clarify the association between the patient’s eating habits, their self-perception, thoughts, and how they view others around them.

- CBT helps patients to make better food choices, become more aware of the health consequences and risks of starvation, and ultimately help them cope with their feelings. The therapist may also support the patient in the creation of a personalized treatment plan.

General Treatment Options

In addition to therapy, those with anorexia will typically be given dietary advice suggesting what foods and supplements should be taken to stay healthy. This is particularly important for young people going through puberty as their AN may cause deficiencies that may prevent them from developing and growing properly. Medication such as antidepressants may be prescribed in combination with therapy to help address comorbid psychological disorders including depression, anxiety and social phobias. However, these are not typically given to those under 18.

Support for Anorexia

If you believe that you may have anorexia, it’s important to see your doctor as soon as possible, as early interventions give you the best chance to recover.

If you’re a concerned friend or family member, then you can let the person know that you’re worried about them and urge them to visit their doctor. There are a range of charities, helplines and support groups available for those with anorexia and their friends and family to get support from.

Sources

- Filippo E. De., Marra M., Alfinito F., et al. (2016). Hematological Complications in Anorexia Nervosa.

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2018). What People with Anorexia Nervosa Need to Know About Osteoporosis. www.bones.nih.gov/.../anorexia-nervosa

- Moore C. A., & Bokor B. R. (2019). Anorexia Nervosa. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459148/

- NHS (2018). Anorexia Nervosa. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/anorexia/

- NHS (2018). Iron Deficiency anaemia. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/iron-deficiency-anaemia/

- Misra M., Shulaman D., & Weiss A. (2013). Fact sheet. Anorexia. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and metabolism. DOI: 10.1210/jcem.98.5.zeg35a

- Sidani J. E., Shensa A., Hoffman B. (2017). The Association between Social Media Use and Eating Concerns among U.S. Young Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. DOI: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.03.021

- Morris J., & Twaddle S. (2007). Anorexia Nerosa. The BMJ. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.39171.616840.BE

- Gorwood P., Blanchet-Collet C., Chartel N., et al. (2016). New Insights in Anorexia Nervosa. Frontiers in Neuroscience. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00256

- Mehler P S., & Brown C. (2015). Anorexia Nervosa – Medical Complications. Journal of Eating Disorders. DOI: 10.1186/s40337-015-0040-8

- Slotwinska S. M., & Slotwinski R. (2017). Immune disorders in anorexia. Central European Journal of Immunology. DOI: 10.5114/ceji.2017.70973

0 Comments