Creating renewable biocement entirely out of waste material.

Cement is a binder, a substance used in construction that hardens, sets, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. When sand and gravel are combined with cement, concrete is produced. Cement is classified as hydraulic or non-hydraulic, with non-hydraulic cement not setting when water is present, while hydraulic cement needs a chemical reaction between dry materials and water.

Cement is one of the most widely used materials on the planet. Cement consumption in the United States was estimated to be 109 million metric tons in 2021.

Cement manufacturing has an impact on the environment at every level of the process. Some examples include airborne pollutants in the form of dust, fumes, noise, and vibration while running equipment and blasting at quarries, as well as damage to the landscape caused by quarrying.

Scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have discovered a method to produce biocement from waste, making the alternative to traditional cement greener and more sustainable.

Biocement is a kind of renewable cement that uses bacteria to create a hardening reaction that binds soil into a solid block.

The NTU scientists have now created biocement from two common waste materials: industrial carbide sludge and urea (from mammalian urine).

They devised a method for forming a hard solid, or precipitate, from the interaction of urea with calcium ions in industrial carbide sludge. When this reaction occurs in soil, the precipitate binds soil particles together and fills gaps between them, resulting in a compact mass of soil. This produces a biocement block that is strong, durable, and less permeable.

The research team, led by Professor Chu Jian, Chair of the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, showed in a proof-of-concept research paper published on February 22nd, 2022 in the Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering that their biocement could potentially become a sustainable and cost-effective method for soil improvement, such as strengthening the ground for use in construction or excavation, controlling beach erosion, reducing dust or wind erosion in the desert, or building freshwater reservoirs on beaches or in the desert.

(from left to right) Dr. Wu Shifan, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Solutions, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, NTU, and Professor Chu Jian, Chair of the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, NTU holding up blocks of biocement made from urea and carbide sludge. Credit: Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

It can also be used as biogrout to seal cracks in rock for seepage control and even to touch up and repair monuments like rock carvings and statues.

“Biocement is a sustainable and renewable alternative to traditional cement and has great potential to be used for construction projects that require the ground to be treated,” said Prof Chu, who is also the Director of NTU’s Centre for Urban Solutions. “Our research makes biocement even more sustainable by using two types of waste material as its raw materials. In the long run, it will not only make it cheaper to manufacture biocement, but also reduce the cost involved for waste disposal.”

The NTU scientists’ research supports the NTU 2025 strategic plan which aims to address some of humanity’s grand challenges, including mitigating human impact on the environment through advancing research and development in sustainability.

Urine, bacteria, and calcium: A simple recipe for biocement

The biocement-making process requires less energy and generates fewer carbon emissions compared to traditional cement production methods.

The NTU team’s biocement is created from two types of waste material: industrial carbide sludge – the waste material from the production of acetylene gas, sourced from Singapore factories – and urea found in urine.

Firstly, the team treats carbide sludge with an acid to produce soluble calcium. Urea is then added to the soluble calcium to form a cementation solution. The team then adds a bacterial culture to this cementation solution. The bacteria from the culture then break down the urea in the solution to form carbonate ions.

These ions react with the soluble calcium ions in a process called microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP). This reaction forms calcium carbonate – a hard, solid material that is naturally found in chalk, limestone, and marble.

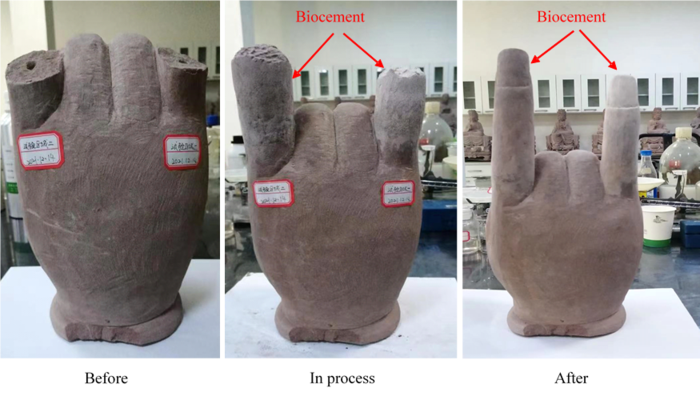

The test specimen of a Buddha hand was provided by Dazu Rock Carvings, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in China. Repair work using biocement was done at Chongqing University, China, by Dr. Yang Yang. The biocement solution is colorless, allowing restoration works to maintain the carving’s original color. Credit: Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

When this reaction occurs in soil or sand, the resulting calcium carbonate generated bonds soil or sand particles together to increase their strength and fills the pores between them to reduce water seepage through the material. The same process can also be used on rock joints, which allows for the repair of rock carvings and statues.

The soil reinforced with biocement has an unconfined compression strength of up to 1.7 megapascals (MPa), which is higher than that of the same soil treated using an equivalent amount of cement.

This makes the team’s biocement suitable for use in soil improvement projects such as strengthening the ground or reducing water seepage for use in construction or excavation or controlling beach erosion along coastlines.

Paper first author Dr. Yang Yang, a former NTU Ph.D. student and research associate at the Centre for Urban Solutions who is currently a postdoctorate fellow at Chongqing University, China, said: “The calcium carbonate precipitation at various cementation levels strengthens the soil or sand by gradually filling out the pores among the particles. The biocement could also be used to seal cracks in soil or rock to reduce water seepage.”

A sustainable alternative to cement

Biocement production is greener and more sustainable than the methods used to produce traditional cement.

“One part of the cement-making process is the burning of raw materials at very high temperatures over 1,000 degrees Celsius to form clinkers – the binding agent for cement. This process produces a lot of carbon dioxide,” said Prof Chu. “However, our biocement is produced at room temperature without burning anything, and thus it is a greener, less energy demanding, and carbon-neutral process.”

Dr. Yang Yang said: “In Singapore, carbide sludge is seen as waste material. However, it is a good raw material for the production of biocement. By extracting calcium from carbide sludge, we make the production more sustainable as we do not need to use materials like limestone which has to be mined from a mountain.”

Prof Chu added: “Limestone is a finite resource – once it’s gone, it’s gone. The mining of limestone affects our natural environment and ecosystem too.”

The research team says that if biocement production could be scaled to the levels of traditional cement-making, the overall cost of its production compared to that of conventional cement would be lower, which would make biocement both greener and cheaper alternative to cement.

Restoring monuments and strengthening shorelines

Another advantage of the NTU team’s method in formulating biocement is that both the bacterial culture and cementation solution are colorless. When applied to soil, sand, or rock, their original color is preserved.

This makes it useful for restoring old rock monuments and artifacts. For example, Dr. Yang Yang has used the biocement to repair old Buddha monuments in China. The biocement can be used to seal gaps in cracked monuments and has been used to restore broken-off pieces, such as the fingers of a Buddha’s hands. As the solution is colorless, the monuments retain their original color, keeping the restoration work true to history.

In collaboration with relevant national agencies in Singapore, the team is currently trialing their new biocement at East Coast Park, where it is being used to strengthen the sand on the beach. By spraying the biocement solutions on top of the sand, a hard crust is formed, preventing sand from being washed out to sea.

The team is also exploring further large-scale applications of their biocement in Singapore, such as road repair by sealing cracks on roads, sealing gaps in underground tunnels to prevent water seepage, or even as cultivation grounds for coral reefs as carol larvae like to grow on calcium carbonate.

Reference: “Utilization of carbide sludge and urine for sustainable biocement production” by Yang Yang, Jian Chu, Liang Cheng, Hanlong Liu, 22 February 2022, Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2022.107443

0 Comments